Do muscles ache after exercise? Yes, it’s very common! This ache, often called delayed onset muscle soreness, or DOMS, happens when you push your muscles a little harder than usual. It’s a normal part of getting stronger.

When you exercise, especially with new or intense movements, your muscle fibers can experience tiny tears. These microtears in muscle fibers are the primary culprits behind that familiar, achy feeling. While it might sound alarming, this exercise-induced muscle damage is actually a signal that your muscles are adapting and getting stronger. This process is closely linked to muscle fatigue, that feeling of tiredness your muscles get during or after a workout.

The feeling of soreness usually peaks 24 to 72 hours after your workout. It’s not typically caused by lactic acid buildup, a common myth. Lactic acid is produced during intense exercise, but it’s cleared from the muscles relatively quickly and doesn’t cause the lingering soreness we associate with DOMS. Instead, the soreness is a response to the microscopic damage and the subsequent inflammation and muscle repair processes.

Image Source: images.theconversation.com

Fathoming the Feelings: What is DOMS?

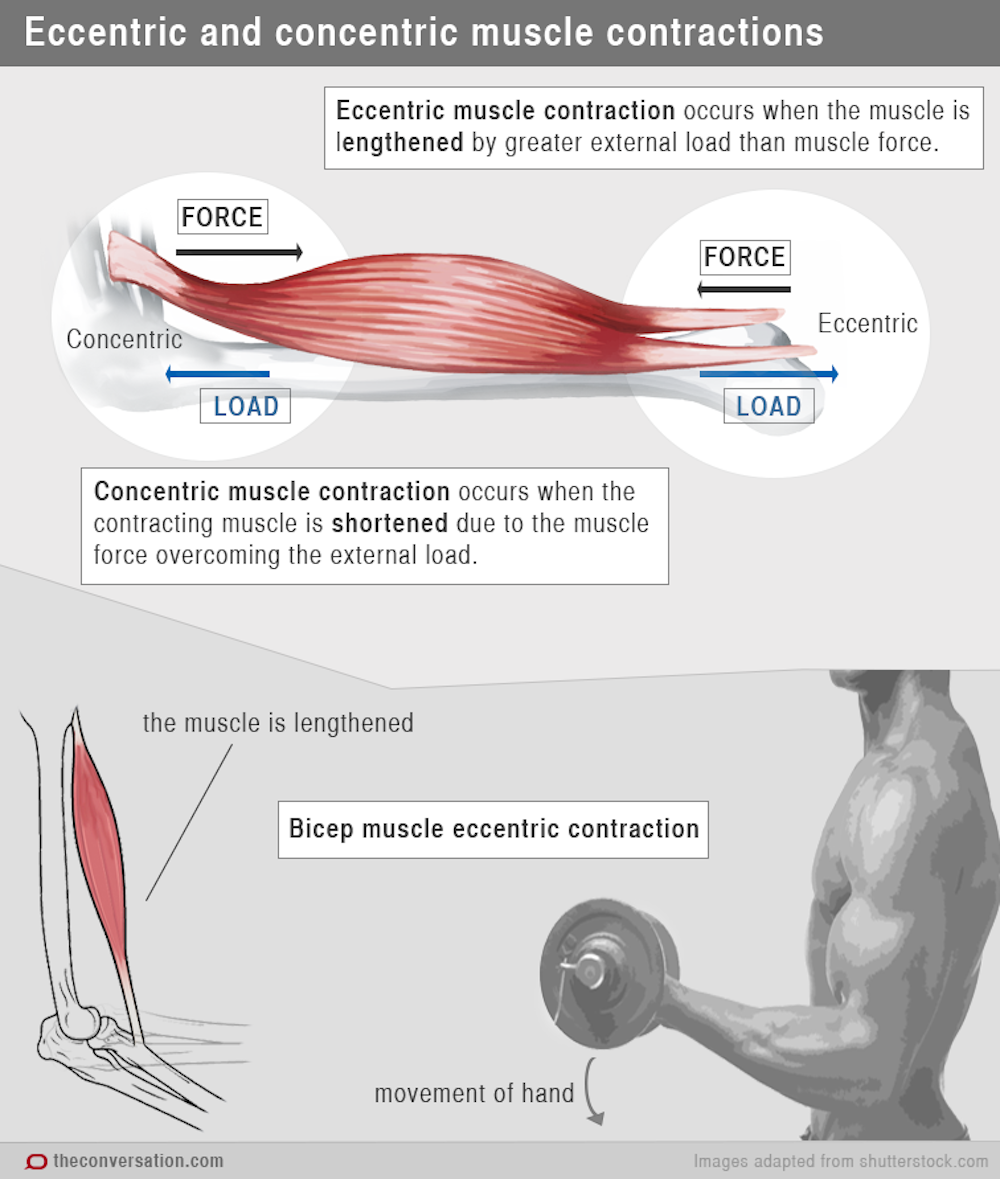

Delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS) is the term for that familiar stiffness and pain you feel in your muscles, usually starting a day or two after a new or particularly intense workout. It’s not an instant pain; hence, the “delayed” in its name. This type of soreness is a normal physiological response to unaccustomed physical activity, especially movements that involve eccentric contractions.

Eccentric Contractions: The Main Trigger

What are eccentric contractions? These happen when your muscles lengthen under tension. Think about the lowering phase of a bicep curl or walking downhill. During these movements, your muscle fibers are working hard to control the motion, and this leads to microscopic damage.

The Microscopic Damage Story

These tiny tears, or microtears in muscle fibers, are the foundation of DOMS. They occur because the muscle fibers were stretched beyond their usual capacity or were subjected to forces they weren’t accustomed to. This damage triggers a natural repair process.

Inflammation: The Body’s Response

Once these microtears occur, your body initiates an inflammatory response. This involves:

- Immune cells: These cells rush to the damaged area to clear out debris and damaged tissue.

- Swelling: The influx of fluids and immune cells can cause mild swelling in the muscle.

- Pain signals: The inflammation and the physical disruption of the muscle fibers send pain signals to your brain.

This entire process, from microtears to inflammation and repair, takes time, which is why the soreness is delayed and can linger for a few days.

Deciphering the Discomfort: Causes of Muscle Aches

Muscle aches after exercise are a complex interplay of physiological events. While lactic acid buildup is often blamed, it’s a less significant contributor to the delayed soreness we experience. The primary drivers are structural changes within the muscle.

Microscopic Tears: The Cellular Level

When you engage in strenuous exercise, especially activities that are new or involve eccentric (lengthening) muscle actions, your muscle fibers undergo stress. This stress can lead to tiny rips or microtears in muscle fibers. These are not usually serious injuries but rather a normal part of the adaptation process.

- Intensified Loading: Muscles that are not used to a particular type of stress will experience more significant microtears.

- Eccentric Movements: Actions where the muscle lengthens while contracting (like the downward phase of a squat) are particularly prone to causing these microtears.

Inflammation: The Body’s Repair Crew

The presence of these microtears signals the body to initiate a repair process. This involves an inflammatory response:

- Cellular Debris: Damaged muscle cells release substances that attract immune cells.

- Immune Cell Infiltration: White blood cells and other immune components arrive at the site of damage.

- Fluid Accumulation: Increased blood flow and the movement of immune cells can lead to mild swelling.

This inflammatory response, while essential for muscle repair, also contributes to the sensation of pain and stiffness.

Muscle Strain: A More Serious Consideration

It’s important to distinguish between DOMS and a muscle strain. A muscle strain is a more significant tear in muscle fibers, often caused by a sudden, forceful movement or overstretching. A strain typically results in:

- Sudden, sharp pain during exercise.

- More intense and localized pain.

- Potentially visible bruising or swelling.

- Limited range of motion.

While DOMS is a general ache, a strain is a specific injury that requires prompt attention.

Muscle Fatigue: The Short-Term Feeling

Muscle fatigue is different from DOMS. Fatigue is the temporary loss of strength and power that occurs during or immediately after exercise. It’s often caused by the depletion of energy stores (like glycogen) and the accumulation of metabolic byproducts (though, as mentioned, lactic acid is cleared quickly and isn’t the main cause of delayed soreness). Fatigue is a feeling of tiredness in the muscles during activity, whereas DOMS is the ache that follows.

The Myth of Lactic Acid Buildup

For a long time, lactic acid buildup was thought to be the primary cause of muscle soreness after exercise. However, current scientific understanding paints a different picture.

What is Lactic Acid?

Lactic acid (or more accurately, lactate and hydrogen ions) is a byproduct of anaerobic metabolism. When your body needs energy quickly and doesn’t have enough oxygen available, it breaks down glucose to produce ATP (energy). This process generates lactate.

Lactate’s Role in Exercise

- Energy Source: Lactate can actually be used as an energy source by other muscle cells and even the heart.

- Short-Term Burn: During high-intensity exercise, the rapid production of lactate and hydrogen ions can contribute to the burning sensation you feel during the activity. This is often associated with muscle fatigue.

- Rapid Clearance: The body is quite efficient at clearing lactate from the muscles. Within an hour or two after exercise, lactate levels typically return to resting levels.

Why It’s Not DOMS

Since lactate is cleared so quickly, it doesn’t explain the soreness that appears 24-72 hours later. The microtears in muscle fibers and the subsequent inflammation are the real culprits behind delayed onset muscle soreness.

The Repair Process: Rebuilding Stronger Muscles

The pain and stiffness of DOMS are indicators that your body is actively engaged in muscle repair. This is a crucial phase in the adaptation process that leads to stronger, more resilient muscles.

Stages of Muscle Repair

- Degeneration (Damage Phase): This is when the microtears in muscle fibers occur. The muscle fibers are damaged, and cellular debris is released.

- Resealing (Inflammatory Phase): Immune cells (like neutrophils and macrophages) arrive at the site of damage. They clear away the damaged cellular components and begin the process of rebuilding. This phase is characterized by inflammation, which contributes to the pain and swelling.

- Regeneration (Repair Phase): Satellite cells, a type of stem cell found in muscle tissue, are activated. They migrate to the damaged fibers, fuse with them, and help to regenerate the muscle tissue. This leads to the thickening and strengthening of the muscle fibers.

- Remodeling: Over time, the repaired muscle fibers are remodeled, becoming stronger and more capable of handling future stress.

Factors Influencing Muscle Recovery

- Nutrition: Adequate protein intake is vital for providing the building blocks for muscle repair. Carbohydrates help replenish energy stores.

- Rest: Allowing your muscles adequate time to recover between workouts is crucial. Overtraining can hinder the repair process.

- Hydration: Staying well-hydrated supports all bodily functions, including muscle repair.

- Sleep: Sleep is a critical period for muscle regeneration and hormone release that aids in recovery.

Who Experiences Soreness and Why?

Anyone can experience delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS), but certain factors can influence its intensity and frequency. It’s not about being “weak”; it’s about the body’s adaptive response.

Beginners and Untrained Individuals

- When you start a new exercise program or try a new activity, your muscles are not accustomed to the load.

- This lack of adaptation means your muscle fibers are more likely to experience microtears in muscle fibers.

- Consequently, beginners often experience more pronounced DOMS.

Returning After a Break

- If you take a break from exercise, your muscles lose some of their accustomed strength and resilience.

- When you resume training, it’s like starting over to some extent, leading to soreness.

Intensity and Type of Exercise

- High-Intensity Workouts: Exercises that push your muscles to their limits, especially those involving new or challenging movements, are more likely to cause DOMS.

- Eccentric Contractions: As discussed, exercises that emphasize the lengthening phase of a muscle contraction (e.g., downhill running, lowering weights slowly) are major triggers for DOMS.

Genetics and Individual Factors

- While not fully understood, there might be genetic predispositions that make some individuals more prone to DOMS than others.

- Factors like age, hydration levels, and overall health can also play a role.

Strategies for Managing Soreness

While you can’t entirely prevent DOMS, especially when pushing your limits, there are effective ways to manage the discomfort and promote muscle recovery.

Active Recovery

- Light Movement: Engaging in light, low-impact activities like walking, cycling, or swimming can help increase blood flow to the sore muscles.

- Stretching: Gentle static stretching (holding a stretch for a period) or dynamic stretching (controlled movements) can help improve flexibility and reduce stiffness. Avoid aggressive or ballistic stretching on sore muscles.

Nutrition and Hydration

- Protein: Consuming adequate protein supports muscle repair. Include sources like lean meats, fish, eggs, dairy, legumes, and plant-based protein powders.

- Anti-inflammatory Foods: Foods rich in antioxidants and anti-inflammatory compounds, such as berries, leafy greens, fatty fish (salmon, mackerel), and turmeric, may help reduce inflammation.

- Hydration: Drink plenty of water throughout the day. Dehydration can exacerbate muscle soreness and hinder recovery.

Other Helpful Practices

- Foam Rolling: Using a foam roller can help release muscle tension and improve blood flow, potentially easing soreness.

- Massage: Professional sports massages or self-massage can also aid in muscle relaxation and recovery.

- Heat Therapy: A warm bath or shower can help relax muscles and improve circulation.

- Cold Therapy (Ice Baths): While more controversial for DOMS, some individuals find short cold exposure beneficial for reducing inflammation.

Important Note: If you experience sharp, sudden pain, significant swelling, or an inability to move a limb, you may have a more serious injury like a muscle strain and should consult a healthcare professional.

Preventing Excessive Soreness: A Balanced Approach

While some soreness is inevitable when challenging your muscles, you can take steps to minimize its severity and duration. The key is gradual progression and smart training.

Gradual Progression

- Start Slowly: If you’re new to exercise or returning after a break, begin with lighter weights, shorter durations, and lower intensity.

- Increase Gradually: As your muscles adapt, slowly increase the weight, duration, or intensity of your workouts. This allows your muscle fibers to adapt without experiencing excessive exercise-induced muscle damage.

Proper Warm-up

- Dynamic Warm-up: Before your workout, perform dynamic movements that mimic the exercises you’re about to do. This prepares your muscles for activity and improves blood flow. Examples include arm circles, leg swings, and torso twists.

- Static Stretching: While static stretching is beneficial after exercise, it’s generally less effective and can potentially be detrimental as a warm-up if not done properly.

Cool-down Routine

- Gentle Activity: After your main workout, engage in 5-10 minutes of light aerobic activity (like walking) to help gradually lower your heart rate.

- Static Stretching: This is the ideal time for static stretching. Focus on the major muscle groups worked during your session. This can help improve flexibility and potentially reduce stiffness.

Listen to Your Body

- Rest Days: Schedule regular rest days into your training program. This allows your muscles adequate time for muscle repair and adaptation.

- Recognize Fatigue: Differentiate between normal muscle fatigue and the onset of excessive soreness or pain. If you feel an unusual or sharp pain, stop the activity.

Hydration and Nutrition

- Consistent Hydration: Ensure you are consistently hydrated, not just during workouts but throughout the day.

- Balanced Diet: Fuel your body with a balanced diet rich in protein, complex carbohydrates, and healthy fats to support overall muscle health and recovery.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: Is DOMS a sign of a good workout?

While DOMS often indicates that you’ve challenged your muscles effectively, it’s not the sole measure of a “good” workout. You can make progress and stimulate muscle growth without necessarily experiencing significant soreness. Pushing yourself too hard consistently can lead to overtraining and injury.

Q2: Can I work out if I have DOMS?

Yes, but with caution. If the soreness is mild, engaging in light, low-impact aerobic activity (active recovery) can be beneficial for blood flow and reducing stiffness. However, if the soreness is severe, or if you feel pain with movement, it’s best to rest or engage in activities that don’t use the affected muscles. Avoid pushing through intense workouts when experiencing significant DOMS, as this can increase the risk of injury.

Q3: How long does DOMS typically last?

DOMS usually begins 12-24 hours after exercise and peaks between 24-72 hours. For most people, the soreness gradually subsides within 5-7 days as muscle repair occurs.

Q4: Does stretching help prevent DOMS?

While a thorough cool-down with static stretching can help improve flexibility and may alleviate some stiffness, there’s limited scientific evidence to suggest that stretching significantly prevents DOMS. The primary drivers of DOMS are microscopic tears and the subsequent inflammatory response.

Q5: What’s the difference between DOMS and a muscle strain?

DOMS is a generalized ache and stiffness that appears 24-72 hours after unaccustomed exercise. It’s caused by microscopic tears in muscle fibers and is a normal adaptive response. A muscle strain, on the other hand, is a more acute injury involving a tear or overstretching of muscle fibers, often occurring suddenly during activity with sharp, localized pain. If you suspect a strain, seek medical advice.

Q6: Will taking protein supplements help with DOMS?

Adequate protein intake, whether from supplements or whole foods, is essential for muscle repair and growth. Consuming protein post-workout can support the recovery process, potentially reducing the duration or intensity of DOMS. However, it’s not a magic bullet, and overall diet and training practices are more critical.

Q7: Is lactic acid buildup the cause of muscle soreness?

No, this is a common misconception. While lactic acid buildup can cause a burning sensation during intense exercise, it is cleared from the muscles relatively quickly after exercise ends. The delayed soreness experienced days later is primarily due to microtears in muscle fibers and the subsequent inflammation and muscle repair processes.